| TITLE | Polygon Boundary | MM 18-8001-0 |

|---|---|---|

| AUTHOR— M.V. Deutsch | ||

| DATE— March 22, 2018 |

| FILING SUBJECTS— | Professional Project |

|---|---|

| Coordinate Geometry |

The convex hull is efficient to calculate with the monotone chain algorithm, especially when combined with the Akl Toissant heuristic. Concave hulls are more complicated and my preferred approach is to use alpha shapes. Gift wrapping should be avoided.

1 Introduction

The convex hull is really quite easy to calculate in two dimensions - it’s almost a baby’s first coordinate geometry algorithm. There are so many different techniques for getting the convex hull that Wikipedia has an entire page devoted to them all: Convex Hull Algorithms. One of the simplest, with reasonable performance, is the ‘Monotone chain algorithm’ (Andrew 1979).

The monotone chain algorithm first sorts the data by the x coordinate, and then passes through the data twice to obtain the top and lower ‘chains’ of the convex hull. This process is illustrated below.

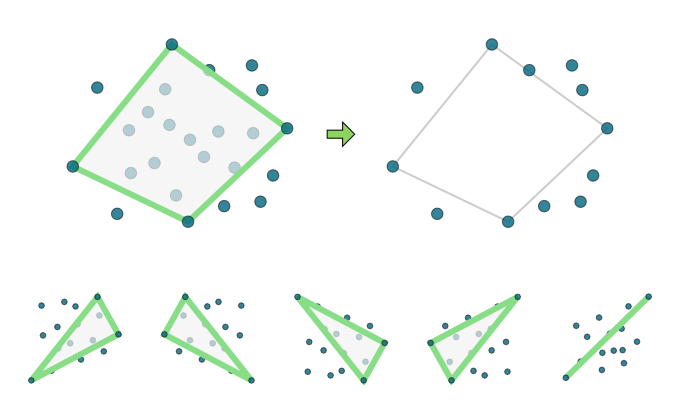

I used this algorithm but first I applied the ‘Akl - Toussaint’ heuristic (Akl and Toussaint 1978).

The Akl Toussaint heuristic is most useful when the points are somewhat uniformly distributed, but it often gets rid of plenty of points quickly. First, the four most extreme points are found at the left, top, right, and bottom. Then all points within that quadrilateral are removed, as they are certainly not part of the convex hull. There’s a couple of edge cases to watch out for:

Here’s an example implementation of the monotone chain algorithm:

struct Point {

double x, y;

inline bool operator<(const Point& other) const {

return (x == other.x) ? y < other.y : x < other.x;

}

};

bool IsLeft(const Point& a, const Point& b, const Point& c) {

return (b.x - a.x) * (c.y - a.y) - (c.x - a.x) * (b.y - a.y) > 0;

}

void ConvexHull(std::vector<Point>& points, std::vector<Point>* results) {

// This function is omitted, because it is boring

if (HandleTrivialHull(points, results)) {

return;

}

// Sort the data lexicographically

size_t n = points.size();

std::sort(points.begin(), points.end());

// Identify the left most points at the lowest and highest y

size_t min_min = 0;

size_t min_max = 0;

while (min_max != n - 1 && points[min_max + 1].x == points[min_min].x) {

++min_max;

}

// Identify the right most points at the lowest and highest y

size_t max_min = n - 1;

size_t max_max = n - 1;

while (max_min != 1 && points[max_min + 1].x == points[max_max].x) {

--max_min;

}

// Construct the lower chain

results->push_back(points[0]);

for (size_t i = min_max + 1; i <= max_min; i++) {

if (IsLeft(points[min_min], points[max_min], points[i])) {

continue;

}

while (results->size() >= 2) {

if (IsLeft(results->at(results->size() - 2),

results->at(results->size() - 1),

points[i])) {

break;

}

results->pop_back();

}

results->push_back(points[i]);

}

if (points[max_max].y != points[max_min].y) {

results->push_back(points[max_max]);

}

// Construct the upper chain

for (size_t i = max_min - 1; i >= min_max; --i) {

if (IsLeft(points[max_max], points[min_max], points[i])) {

continue;

}

while (results->size() >= 2) {

if (IsLeft(results->at(results->size() - 2),

results->at(results->size() - 1),

points[i])) {

break;

}

results->pop_back();

}

results->push_back(points[i]);

if (i == 0) break;

}

if (points[min_max].y == points[min_min].y) {

results->pop_back();

}

}2 Concave Hull

The main point of this little project, was to improve the routine for calculating the concave hull, that is the hull which uses more segments and allows concave angles to more closely follow the points. There are a couple techniques for getting this polygon - and the first I tried was based on using the k nearest neighbors of a point, and essentially the Graham scan algorithm in that local neighborhood, (Moreira and Santos 2007) While initially promising, this algorithm had problems with very large datasets and unfortunately was a failure for my use case.

The algorithm, as suggested above, requires determining the k nearest neighbors of a bunch of points, so of course an accelerator is required. Moreira 2007 recommend using a KD-Tree, which is a good suggestion. But even with a KD-Tree you first have to pay for generating the tree, but you also have to pay every time you need to find the neighbors. But the real killer of this algorithm is that it’s very possible to generate intersections. And you have to check for them, and then fix them by rewinding and increasing k. This eats up a ton of time when the number of points is very large (>100,000), and I quickly had clients complaining about their computer locking up when they tried to get the boundary of some topography contours, or other huge datasets.

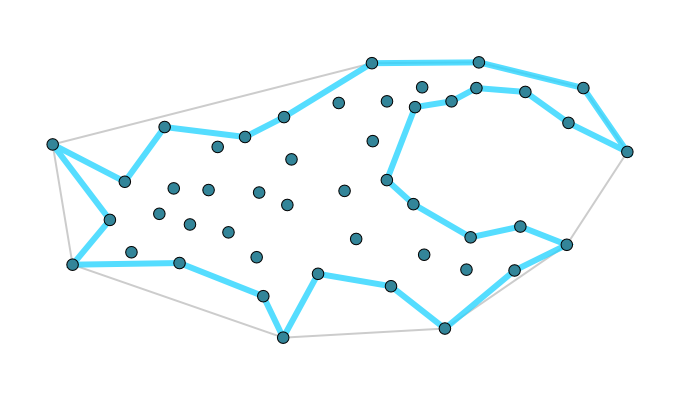

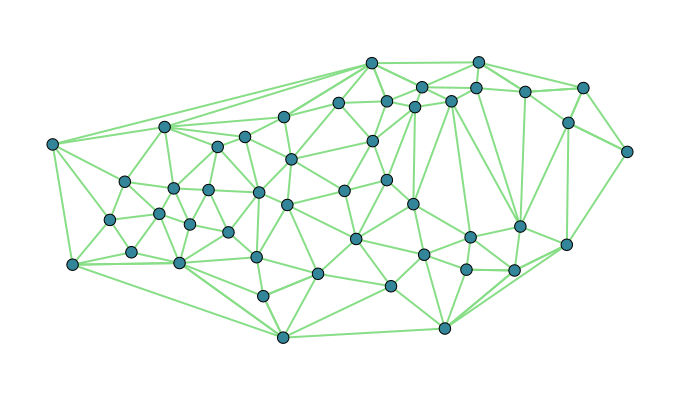

So back to the drawing board, I turned to ‘alpha shapes’ which uses the Delaunay triangulation of the points (Akkiraju et al. 1995). For our point set the Delaunay triangulation looks like this:

The idea of alpha shapes is really simple, we just throw out triangles that have really long sides, and union the rest together into the resulting polygon. This is ideal because the Delaunay triangulation can be computed in \(\mathcal{O}(n \log(n))\) time and many really good algorithms exist for that. The final boundary can then be extracted relatively easily especially if you calculated the ‘neighbor’ information in the triangulation. That is, you don’t actually union all of the triangles together explicitly.

Another advantage of this method, beyond its speed, is that it can handle multiple disparate chunks, and even recreate holes in the input point set. Also, to help set the mysterious ‘alpha’ parameter, I made it so the Delaunay triangulation was calculated once and then the user could change ‘alpha’ and see the resulting polygons instantly, even with hundreds of thousands of points. This worked out great.